|

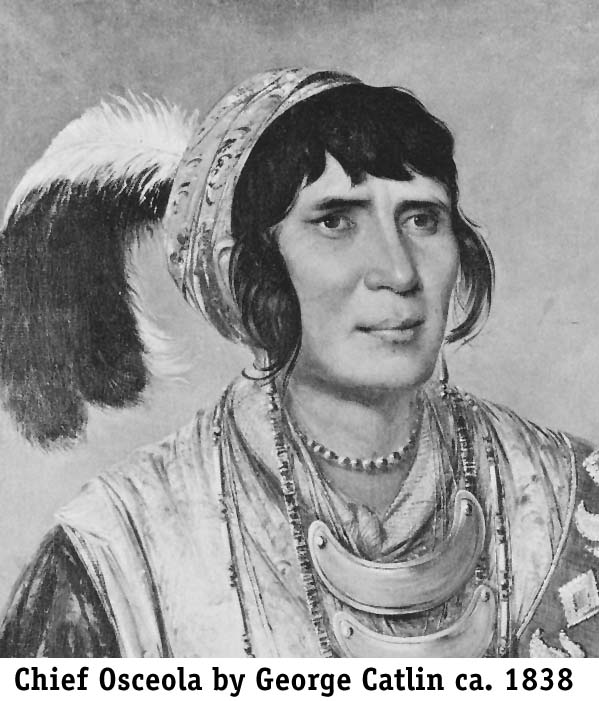

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823 shortly after statehood created a reservation of four million acres in central Florida south of Ocala, but the treaty did not satisfy either side. A drought in 1827 forced the Indians outside of their Florida reservation boundaries. At a conference on May 20, 1827, the Seminole Indians again rejected a treaty to move west of the Mississippi River. Then in 1829, Andrew Jackson was elected President, and proposed to move all Indians west of the Mississippi. On May 28, 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act to do so. The Treaty of Fort Gibson in 1833 specified that the Indians had three years to move to Oklahoma. This lead to the separation of the Seminoles (The Trail of Tears) into the Oklahoma and those who remained, the Florida Seminoles. Also in 1833, Osceola emerged as an important Seminole leader. There are many pros and cons about the effectiveness of Osceola's leadership; at any rate, in June of 1835 there was an Indian-military skirmish at Hickory Sink near Gainesville, Florida. Then in August, a military courier named Private Dayton was killed near Fort Brooke (Tampa). Indian Agent Wiley Thompson set December 1, 1835 as the final date for Seminole Indians to sell their cattle before moving. Charlie Emathla (Tuko-see Mathla) brought his cattle in and was ambushed while returning home. Osceola and the Mikasuki were blamed for this act. Emathla's money and goods were left to show that robbery was not the motive.  It all came to a head on December 28, 1835, with two events. First, Major Francis Dade, who had recently been transferred from Key West, was en route with two companies from Fort Brooke (Tampa) to Fort King (Ocala). They were ambushed near Bushnell, Florida and 108 soldiers were killed. Second, Indian Agent Thompson and others were killed at Fort King as they strolled after dinner. Two days later, General Clinch was attacked crossing the Withlacoochee River. These and other incidents led to the Second Seminole War (1835 - 1842). The Second Seminole War was by far the most significant of the three Seminole Wars. It must be remembered that the Indian lands were constantly being taken from them, treaties made in a language they could not read much less understand; then blatantly broken. The principle difficulty at this time was the insistence that all Seminoles be moved to the Oklahoma Territory Indian Reservation to live among their life-long enemies in a completely alien environment. At this time, there were still about 6,000 Seminoles in Florida. Those that remained became the Florida Seminoles. Closer to the Keys, on January 6, 1836, the family of William Cooley was killed at their home on the New River (Fort Lauderdale). Cooley himself was away from home at the time. As a result of this hostile atmosphere, the Cape Florida lighthouse keeper John DuBose took his family to Indian Key and then to Key West. Many other Keys families also fled to Key West for protection. Indian Key, with six cannons, petitioned for additional protection. When the petition fell through its inhabitants decided to remain. Indian Key, Key Vaca and Key West were the principal settlements in the Keys at this time. On July 23, 1836, Cape Florida's assistant lighthouse keeper Irwin Thompson and Aaron Carter, a Negro, were attacked and driven into the lighthouse. The Indians set fire to the wooden door and stairs, and Thompson and Carter climbed out onto the catwalk to survive. Thompson threw a keg of gunpowder down the inside and almost extinguished the fire. Carter was killed. Thompson was rescued by the crew of the ship Motto and recovered in Key West. A short time later, the Indians destroyed the unattended garden of the Carysfort lightship keeper on Key Largo. They then moved south to attack the schooner Mary near Tavernier. In 1837, they shot and killed Captain John Whalton and one crewman of the Carysfort Lightship when they came ashore for fuel wood. Commodore Alexander Dallas, commander of the West Indies Squadron, temporarily set up at Cape Florida until he could build a fort on the mainland. The fort was named Fort Dallas. The army resented a Fort being named after a naval officer. Lieutenant Colonel Harney and his 2nd Dragoons also used the fort while pursuing Chief Chekika (The spelling of the Chief's name varies.) after the Indian Key raid. On April 24, 1838 Colonel Bankhead established Fort Lauderdale on the New River. The same year the U.S. Revenue Cutter Campbell established its headquarters on Tea Table Key just north of Indian Key. The Indians of south Florida had traded with the Spanish from early times. Many spoke Spanish fluently. Part of the trading was participating in the wrecking activities along the coasts. Because of their association with Cuba, this group was sometimes referred to as "Spanish Indians," and Chief Chekika was probably their last leader. On July 23, 1839, Chief Chekika with about 160 warriors surprised Lt. Col. Harney's Dragoons on the Caloosahatchee River. The Colonel and 14 soldiers escaped. This was probably the first specific incident that was definitely ascribed to the "Spanish Indians." Some of the earlier episodes could have been their doings also. On August 7, 1840, Chekika led about 17 canoes loaded with Indians on an attack of Indian Key. Dr. Perrine and six others were killed and the island sacked, looted and burned. Lt. McLaughlin of Tea Table Key had deployed his forces to Florida’s west coast, so only the sick and a few caretakers remained on the Key for defense. Col. Harney, who was then at Fort Dallas, gladly accepted the assignment to hunt down Chekika, after barely escaping with his life on the Caloosahatchee River. With 16 canoes, he surprised Chekika in the Everglades and killed him. Slowly, the Florida Seminoles were being severely reduced as an effective force. One of their leaders, Osceola, had been captured while under a flag of truce. Thirty-three other outstanding Florida Seminoles, including Principal Chief Micanopy and Wild Cat, were tricked and imprisoned the same way. Osceola died in prison in Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. The U.S. forces with about 5,000 troops continued their efforts. By March of 1841, all of the citizen soldiers were dismissed and on August 14, 1842, Col. Worth, in conferences at Fort King and Cedar Key, announced the war was over. Until the Vietnam War, this was the U.S.’ s longest war. It too did not end in a decisive victory. The total U.S. cost of the war is estimated at $40 million and about 1,600 military deaths. The Florida Seminoles probably never had more than 1,500 warriors. They were scattered about Florida with most of those remaining being driven into the Everglades. Make no mistake, the federals sent some of their most qualified to win the war. The list includes "Old Rough and Ready" Zachary Taylor and "Old Fuss and Feathers" Winfield Scott. The brutality of war notwithstanding, there were Florida's gains at the expense of Indian losses: considerable exploration and mapping; many trails and roads established throughout; many forts that served as starting points for towns; considerable amount of dollars spent. The money was spent directly and indirectly through employment of civilians, and payment for rent, food, supplies and relief. Another Florida benefit of the Indian war was the Armed Occupation Act of 1842, which gave homestead rights to white civilians. Following the Second Seminole War there were about 500 Florida Seminoles remaining. A two and one half million acre “hunting and planting” preserve was established in the Lake Okeechobee area. The principal chief was Billy Bowlegs and Sam Jones could be called the second in command. In 1849 there were two acts of violence on the part of five Seminole renegades. This elicited quite a scare of another Indian War, however it was settled by the Seminoles indicating their desire for peace. Then in December of 1855 a party of U.S. reconnaissance surveyors were mapping the Seminole reserve in the Big Cypress. They came across a Seminole farm and for some reason destroyed all the banana trees, at least they were the ones blamed. Chief Billy Bowlegs retaliated by wounding and killing several soldiers and the officer in charge. This became known as the Third Seminole War (1855 - 1858) whose center of action was mostly in the Fort Meade, Florida and Big Cypress areas. The U.S. pressed about 1,500 soldiers (regular plus militia) into service against the approximate 100 Seminole warriors. This and others were more or less Vietnam type wars. Colonel Loomis declared the war over on May 8, 1858. Billy Bowlegs and 163 others had been sent west. Sam Jones remained hidden in the Everglades with about 200 men, women and children. Both sides had about the same number of dead. I know of no specific attacks in the Keys, however as you can imagine, after the Second Seminole War fear of another raid similar to Indian Key spread throughout the Keys. Dr. Joe Knetsch of Tallahassee has been providing us with documentation of these concerns and actions. There is mention of a fourth Seminole War (1880s), but it was not a war. The Florida Seminoles appeared to have just disappeared into the Everglades from 1860 to 1880. A few came out to trade and peace seemed to be at hand. In the 1880s a group of white men were fired upon by an alleged band of Seminoles in the Everglades. United States troops were dispatched from the West, but nothing much became of the incident. By 1908, the Florida Seminole population was given as 275. Since they were no longer a threat, broke and had little land of value; the hate, greed and prejudice began to disappear. By an act of Congress in June of 1924, all Indians were given citizenship status. The Florida Seminole were divided into those who lived near Lake Okeechobee, the Cow Creek division, and those who lived in the Big Cypress, Everglades and Tamiami Trail, the Cypress division. The Florida Seminoles were granted various reservations such as the Hollywood, Brighton, Big Cypress and Mikasuki on the Tamiami Trail. The Mikasuki officially became a separate tribe (as they always were) by a federal law in 1962. The spelling was changed to Miccosukee at that time. John Lee Williams spelled it Mickasooke in 1837. Before closing, one should remember that about two-thirds of the generic Seminoles remain west of the Mississippi River. Only traces of the Black Seminoles remain. Some were transported to the Bahamas by wreckers. Tavernier Key was a popular embarkation point. Many went to Oklahoma Territory and then on to Mexico, etc. Now (modern): I continue to stand by my research that 'Seminole' was an English given name by an American Indian Agent some time in the 1770's. To my knowledge, absolutely none of the original Indian tribes used the names that we designated them by - today they do however. Using the name of 'Seminole' today there are: 1) Seminole Tribe of Florida, 2) Oklewaha Band of Seminole Indians, 3) Okelevueha Band of Yamassee Seminole Indians, and 4) Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. There is of course the: Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida. The Uchiti's name are: Yuchti Tribe of Oklahoma. The Creek's are: Creek Indians of Texas. I do not find Mushogee per se, but here is the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma, I believe these are Creek descendants. Many say the original Seminole language is almost entirely Moshogee. I do not find any Hichiti's with that spelling, but did find: 1) Yuchi (Euchee) Tribe, Oklahoma and 2) Yuchi Tribal Organization, Oklahoma. With this postulated, their history is still preserved in the proper names of towns, villages, rivers, lakes, etc. [Jerry 4-1-2010] Sources: Florida’s First People, Robin C. Brown, 1994;

History of

the Second Seminole War 1835-1842, John K. Mahon: The Seminole and

Miccosukee

Tribes. Harry Kersey, 1987; The Billy Bowlegs War 1855-1858, James W.

Covington,

1982; The Black Seminoles, 1996, Kenneth Porter; Fearless and Free,

George

Walton, 1977.

------End-------- BACK to PAGE ONE |