|

THE

By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

THE

By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

| Millions of vehicles have conceivably passed through Islamorada and overlooked the 1935 Hurricane Memorial. It is innocent enough in appearance, yet eloquent and highly significant in legacy as a memorial. For those who might wish to visit the site, it is located between the old State Road 4A highway and the present U.S. 1 at mile marker 81.5, across from the library. It was dedicated November 14, 1937 as The Florida Keys Memorial and memorializes the World War-I veterans and civilians who perished in the 1935 hurricane. The U.S. Department of Interior placed it on the National Register of Historic Places on March 16, 1995. The Harvey Seeds Post of the American Legion in Miami took the lead in obtaining $3,779 as a contribution of which $2,500 was cash. The finished cost was around $12,000. The memorial was designed by the Florida Division of the Federal Art Project and was constructed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1937 as Zone 3, Project Number 2217.

After the 1935 hurricane, to build a new school Hugh Matheson exchanged

land he owned on the highway for the beach site of the destroyed

school.

W.P.A constructed the new school and was to be a combination hurricane

shelter and school. A second almost identical structure was also

constructed

in Tavernier. The Matecumbe school is now the Islamorada Library and in

Tavernier it is the health department. For a detail discussion of this

sister WPA school project, please Click

Here. The exact person who came up with the idea of the hurricane memorial is not known. The new Matecumbe school building site was plenty large, and a short access road for the school was needed from the old highway. A small triangular site east of the railroad right-of-way was separated for the memorial site in exchange for building the access road to the school, but land ownership did not change. Art and design was done by the WPA Federal Art Project personnel. The memorial is still owned by the Monroe County School Board. For the memorial, the center was dug down to bedrock and a base was made of stone and concrete 65 by 20 feet. From the base five broad steps lead to an elevated flooring area. It is covered with coral slabs known as "keystone" quarried from either the Windley Key or Key Largo Quarry. The original structure stopped at the lower step. Later, the original crushed coral rock area between the flagpole and the steps was paved with artificial keystone material. A concrete sidewalk was also added and decorative vegetation added. There is a crypt made into the upper level that contains the skeletal bones and cremated remains of many of the veterans and citizens who perished, some after the 1935 hurricane. A 22-foot long ceramic tile map by ceramicist Adela Gisbet of the Keys from Key Largo to Marathon is inlaid into the cover of the crypt. The native rock-covered obelisk of the memorial rises 18 feet skyward above the dais with a relief sculptured tidal wave and palms bending under the force of the terrific winds. The glyphic Mayan style design was by Harold Lawson and developed by Lambert Bemlemans. Other WPA artists involved were William Shaw, Allie Mae Kitchens, Emigdio Reyes and Harold Lawson.

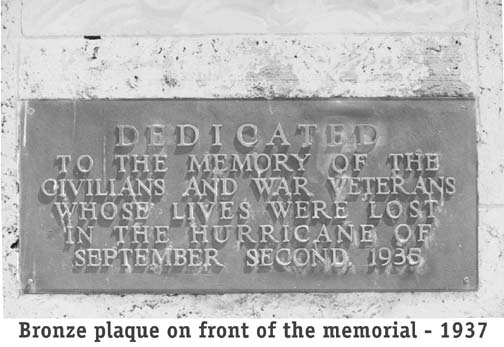

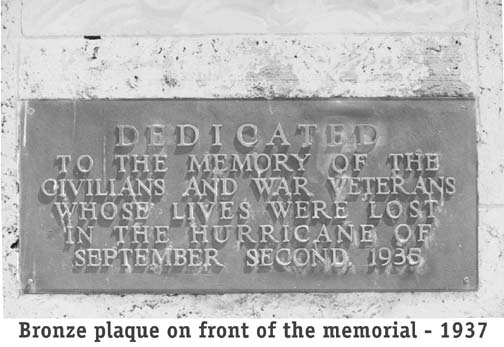

Below the sculpture is a bronze plaque by artist John Klinkenberg

inscribed:

"Dedicated To The Memory Of The Civilians And The War Veterans Whose

Lives

Were Lost In The Hurricane Of September Second 1935." Nine-year-old

hurricane

survivor Faye Marie Parker unveiled the monument on Sunday, November

14,

1937 as about 5,000 officials, guests and visitors looked on. Many lost their lives on that fatal September 2, 1935. In the Matecumbe area, the lives lost were those of visitors, veterans and residents. Of the Islamorada Russell family, which totaled over 70 members, only a few remained the following day. The late County Commissioner Harry Harris, while not a hurricane victim, was later interred in the monument. His remains have since been removed and interred at Harry Harris Park. Although the exact number is not known, it is estimated that the cremated remains of some 190-storm victims lie there. Again figures differ as two years had elapsed since the open site cremations and the dedication in 1937. There exist different totals of the loss of life in the Keys, and in truth the total will never be known. One of the often used sets of figures are those of the coroner but the report is not dated. It does agree with those on the Veterans Storm Relief chart dated 1936. At the Congressional Inquiry H.R. 9486 in March, 1936 the Administrator of FERA, Conrad Von Hyning, presented the below deposition of bodies as of March 1, 1906: VETERANS CIVILIANS Permit me to step back to the occasion of why so many World War I veterans were in the Matecumbe area. In 1928, the Overseas Highway was linked to Key West by a ferry boat system from Lower Matecumbe Key to No Name Key. To complete the highway without the use of ferries, the Army Corps of Engineers had estimated a cost of $7.5 million. Times were hard and Monroe County was already indebted to the limit, so it submitted a $10.7 million request to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to bridge this water gap with a highway.

Time passed and finally the RFC submitted the request to Washington in

October, 1932. President Roosevelt was trying to pull the nation out of

the Depression and he and Congress had given the Board of Public Works

some $3 billion for various work projects. In 1933, the government

created

the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). Two years before,

Washington

D.C. had been under siege by what was known as the "Bonus Army" which

was

composed of World War One (WW-I) Veterans made desperate by the Great

Depression.

They were negotiating for promised entitlement bonuses payable in 1945

and were encamped in front of the capitol. Unemployed WW-I veterans staged hunger marches and demonstrations in several cities, but the most famous was the Bonus Expeditionary Force in Washington, D.C., in June, 1932. A WW-I bonus law was passed in 1922, but vetoed by the President. In 1924, Congress overrode the presidential veto and gave every veteran a certificate payable in 1945. The nation entered the depression and in 1931 the vets demanded to be paid the bonus early. In June, 1932, about 15,000 veterans descended on Washington to convince the Senate to pass the bill. They were unsuccessful and finally President Hoover chased the "bonus marchers" out of Washington with bayonets and tear gas. Some say this action "put Roosevelt in the White House." Anyway, FERA was created in May, 1933 and various work programs and camps were established throughout the country. The events leading to the presence of the veterans in the Matecumbe work camps followed this scenario. Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas badly needed repair and the veterans seeking work were creating adverse public reaction in Washington. Solution: Send the vets to Fort Jefferson to repair it. This would get the fort repaired and the vets out of Washington. Three hundred vets were sent, but were retained in Jacksonville awaiting permission from the Navy to repair the fort. While waiting, the vet's mission was changed to the Upper Keys. The Great Depression was on and Monroe County had declared bankruptcy. Florida's first FERA administrator, Julius Stone, had set up a second office in Key West. He observed that Key West was missing the important tourist trade and declared it could be the Gibraltar of the South. To do this, it would need a better highway system with no car ferries. FERA knew that Monroe County needed an efficient highway built, so many vets were diverted at Jacksonville to the Upper Keys. They were to build a highway bridge to replace the car ferry. The Florida State Highway Department was in charge of construction and the vets were to perform the construction. All of the Fort Jefferson and No Name Key vets were sent to the Upper Keys in May, 1935.

Three camps were constructed in the Upper Keys beginning in November,

1934.

Camp 1 was located on Windley Key, Camp 5 on the upper end of Lower

Matecumbe

Key and Camp 3 on the lower end. Each camp could house about 250

workers.

The small, but main headquarters was in the Matecumbe Hotel on Upper

Matecumbe

Key. The Lenoy Russell Hotel on Windley Key was converted into a small

hospital. The number of veterans present would about equal the 1935

census

reported population of the entire Upper Keys -673. Note: There were

other

veteran camps in Florida. For example, Camp 2 was in St. Petersburg and

Camp 4 was in Clearwater. South Carolina also had camps. The Key

Veteran

News, a local newspaper, was printed weekly in Homestead often

containing

columns from all the camps. At the time of the hurricane, the Keys' veteran camps were organized as followers: Will Harnica, Burt Davis and W. G. Robertson were camp 1, 3 and 5 camp supervisors, respectively. O. D. King, owner of the Rustic Inn, was the transportation officer and Edney Parker was the sanitation officer. Ray Sheldon, the Key's FERA project supervisor, reported to C. Van Hyning, supervisor of all Florida FERA camps. F. B. Ghent was the Florida Director of FERA. Project supervisor, Ray Sheldon, testified at the March, 1936 Congressional Inquiry that he had requested a relief train at 1:37 p.m. on Monday as his barometer indicated a serious drop in pressure. Sheldon himself returned on Sunday from his honeymoon in Key West. It being a holiday weekend, railroad crews and train components had to be assembled. Leaving Miami around 4 p.m. and experiencing several serious delays, the train arrived at Islamorada only a few minutes before the tidal surge at about 8:20 p.m. Sheldon testified that the water rose five feet inside the train's cab while he was talking with the crew. As the track averaged a minimum of seven feet above sea level, he estimated that the surge was 12 foot at his location. Sheldon further testified that many of the 684 veterans present for pay on August 30 were away for the Labor Day holiday. He answered "Yes, sir." when asked by the chairman, "Out of 684 men, there were, approximately, as you say, 161 showed up for breakfast?" Some estimate that as many as 350 were in Miami and Key West for festivities. Additional testimony revealed that "There were 91 in jail at 10 o'clock Monday, and I know there were 11 who had stolen a suburban truck and headed up to visit the President." All that remains of the bridge project are three completed bridge piers and a few unfinished piers. These can be seen just off the bay side of the north end of the Channel Two bridge at mile marker 73.5. They look like three gray coffins sitting in the bay across from the Calusa Cove Marina. The plan was to build a highway bridge to Greyhound (Fiesta) Key and, if successful, on to Grassy Key. Eventually, concrete bridges would be built to No Name Key, thus eliminating the two water gaps.

After the hurricane, there was a congressional bill for financial

relief

for the surviving dependents. The bill was necessary as the veterans

and

their families were not covered by state or federal compensation laws.

A copy of H.R. 9486 can be seen in the Key West Library. In 1936, the

bonus

was paid -too late for those who lost their lives in the Upper Keys.

Their

families were somewhat compensated. So, the next time you cross the

Channel

Two bridge at mile marker 73, look about 800 feet to the west (Gulf

side) for the remains of eight bridge piers built by the WW-1 veterans

in the water and remember this part of Keys history. To my knowledge,

this is the only remaining artifacts of their work in the Keys. The

small island (Veterans Key) just north of the piers grew from an

earthen approach being constructed to connect the piers and Lower

Matecumbe Key.

For more photos of the monument, please Click Here. The Hurricane Memorial is an appropriate place to visit on Memorial Day, Veterans Day, Labor Day and/or any September 2. To see other WPA artist works click HERE, or Return to the Hurricane History Homepage, Click HERE. |