|

BLACK HISTORY By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

BLACK HISTORY By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

Our first recorded history of the slave trade was the Spanish using

Indians

for their early colonization projects in the West Indies. In 1494,

Columbus

shipped 500 Carib Indians to Spain to be sold and the proceeds sent

back

to Hispaniola in the form of livestock. The first recorded US account

that

I know of was by an unidentified Dutch ship unloading "20 negars" at

Jamestown,

Virginia in 1619. The slaves had been hijacked from a Spanish ship

bound

for no other than the West Indies.

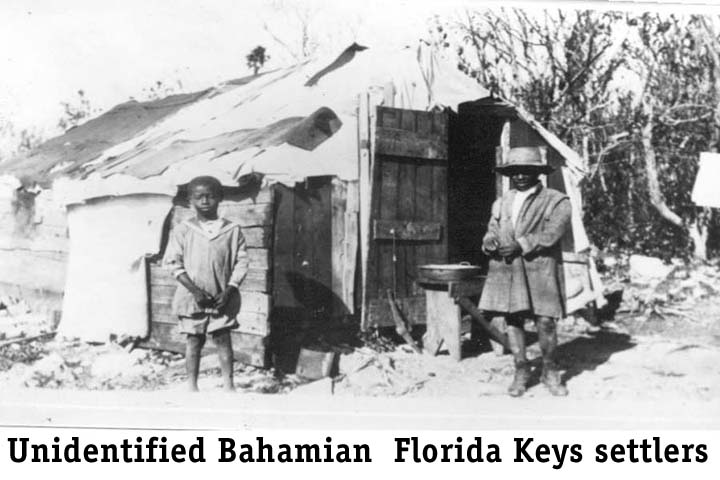

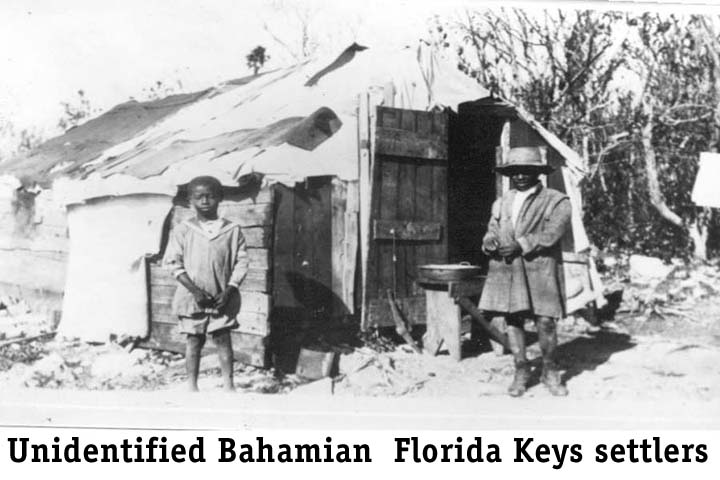

Early Blacks in Monroe County were from the Carolinas, Georgia, Cuba and the Bahamas. The first official count was in 1830 when the government census showed 83 Free Negro and 66 slaves. This is significant as the total population was 517, therefore 28.8 percent were Black. For Monroe County many of the Free Blacks were from the Bahamas, but how did they get there? By nature of its location on the slave trade triangular shipping route and its agricultural economy, the Bahamas became dependent on African slaves. Affluent whites moving to the Bahamas also brought many slaves with them. For example, a large group of new white settlers reached New Providence, Bahamas in 1740. From a list of arrivals there were about 1800 of which 443 were slaves. That is about 25 percent slaves. Before and after the Revolutionary War, affluent white British sympathizers moving to the Bahamas brought many slaves with them. More arrived after Florida changed from British to Spanish ownership in 1783. Many additional Negroes fled there to escape slavery and became "free Negroes." The British Empire passed an act in 1833 abolishing slavery in its Bahamian colony. The systemization of the British West Africa Slave trade was well established in the late 1600s. Of course the 1833 Emancipation Act gave them their freedom in the Bahamas. Under Bahamian law, the former slave owners had to provide their former slaves with an apprenticeship program. They were provided work not to exceed 45 hours per week and were fed and clothed. The apprenticeship ended on August 1, 1838 and the former slaves became free, but freedom was no guarantee of equality. Monroe County was in its infancy then having been created in 1823. Monroe County accounts written of the 'coontie' industry (mostly on the mainland) used slaves. Cooley, Ferguston and Fitzpatrick had slaves to work their plantations. Charles Howe and Jacob Housman had slaves on Indian Key. However, the largest increase was precipitated by the construction of Fort Taylor and Fort Jefferson which began in 1845. The 1850 census revealed 126 Free Negroes and 431 slaves of the total population of 2,645. In percentages this is a decrease to 21, however note the ratio of Free to slave. The Free increased by 52 percent and the slave increased by 553 percent. What's more, Jefferson B. Browne wrote prior to 1845 there were less than 200, slave and free Blacks, and increased to over 550 in 1850. Slave owners simply rented their slaves out for government construction of the forts. Part of Commodore Porter's mandate in 1823 was to interdict the maritime slave trade. Monroe County had several incidents of illegal maritime slave trade. The first I know of was the wreck of the Spanish Slaver Guerrero and the British HBM Nimble on December 20, 1827. The slaver had 561 slaves and a crew of 90 aboard. Wreckers got the Nimble off the reef and attempted to send the Blacks to Key West. Of those who survived the wreck, 388 were hijacked and taken to Cuba, but 121 arrived in Key West safely. It is an interesting, but lengthy story involving the Americans, British and Spanish. President John Quincy Adams became personally involved in the negotiations. The surviving Blacks were eventually transported to Liberia. The New York Tribune reported from the Journal of Comerce in July 1860 that five slavers were captured off the coast of Cuba. The Wildfire, Wilhamar, and Bogota were taken to Key West. In addition to the above, the Echo, Huntress, Joven Antonio, Lyra, Kimball, Sultana and Toccoa were taken to Key West. The freed slaves were housed in 'baracoons' and processed for transportation to northern ports. In general the early occupations of Blacks in Key West were fishing, sponging, salt manufacturing and turtling. Later Key West city directories listed Black male occupations as: cigarmaker, seaman, sponger, carpenter and laborer. Black females were usually listed as seamtress or laundress. My personal research has been focused on the Upper Keys. The early settlement of Newport and the black settlers who followed are good examples of forgotten contemporary history. We are quick to preserve buildings, artifacts and collect all forms of things that people use, but this is about people and their place in historic preservation. From the already discussed dates, not much in the way of settlements existed in the Upper Keys before 1838 and 1865, except for Indian Key, where there were Negro slaves. In the early days there were Bahamian and American Blacks in the Upper Keys. The Bahamians far outnumbered the Americans because they had been coming to the Keys for centuries, not necessarily to live permanently, but to fish, turtle, cut lumber, wreck, et cetera. In a 1790 Spanish letter, Luis Fatio requested the Spanish Crown to set up military stations on Rodriguez and Tavernier Keys to keep the Bahamians out. When steamships, which did not wreck as often, replaced sailing vessels, many Bahamians joined others who had been venturing to the Keys for years. Instead of engaging in wrecking, these settled to fish and farm. Farming was difficult in the Bahamas, so the Keys did not appear especially difficult for the tough Bahamians. They knew how to plant on this type of land and they brought with them their own commonly used trees, vegetables and fruits. They were also noted for their masonry skills with limestone.

One possible example was a Bahamian who 'jumped' ship off of Windley

Key

and worked with Charles Cale quarrying coral rock. He is respectfully

known

only as J. P. If he had a last name, no one asked.

Some of these Bahamians settled in the Newport area. Azariah (38) and Sarah (34) Pinder and their 6 children farmed the area. Also recorded were Cornelius (28), a seaman, and Amy Pinder (29). Homestead grants were requested and obtained by Sylvanius Pinder in 1883, Jeremiah Pinder and Cornelius Pinder in 1888 and William H. Sawyer in 1888. Sawyer had 149.23 acres, which he sold to Joseph H. Anderson in 1905, who sold 39 acres to Joseph A. Anderson in 1918. This 39 acres is today's Hibiscus Park. The Lance-Hall Corporation eventually sold many of the individual lots in the 1950s. Newport also had the first recorded Methodist ministry in 1885, followed by the Planter Barnett Chapel in 1886. These ministries were served by circuit riders. The first school on Key Largo was opened in Newport in 1884 with a Mrs. Gould teaching 9 students. We do not know if there were any blacks among these families, but this was the start of land ownership in Newport. It is known that there were four basic black settlements in the Upper Keys during the early 1900s; however, isolated black families lived throughout Key Largo in places like Seaside and Planter. The first group was located in the area of today's Ocean Reef where the black Bahamian family of Tom Lowe, Sr. had a large farm. South of that was the early settlement of Basin Hills, but we are not certain if or how many blacks were there. Farther south was the second settlement, the aforementioned Newport out of which the white settlers had moved by 1910. In recent years, surviving artifacts, such as a bee-hive shaped community oven and water cisterns, were destroyed. William Clark of Newport, recently showed me the only known artifacts remaining. These consist of a large, rock walled-in area near the ocean and a water cistern by the shooting club. The general concensus is that the walled-in area was to keep pigs or goats because it is not large enough for cattle. Clarence Alexander of Newport recalls black Bahamian families living along the old highway about 1932. The names he recalls were Anderson, Davis, Smokey, Stone, Clark and Gibson. In the 1930s, Hubert (Mac) McKenzie, a contractor and wholesale dealer in petroleum products, had a number of blacks working for him in Tavernier, as did Dr. Tallman on Plantation Key. This was the third settlement and where Clarence Alexander first settled. Farther south on Upper Matecumbe was the fourth settlement. Contractor Alonzo Cothron had a number of blacks working for him. Bahamian Kathleen Dean first worked for Alonzo when she came from Key West. Some of these blacks may have remained in the Keys after constructing the Flagler railroad from 1905 to 1912. The following are 1992 interviews with three of the oldest black residents remaining in the Key Largo area. We are indebted to them for this valuable piece of legacy.

First was Clarence "Pop" Alexander who purports to be the first

permanent

American Black to settle in the Upper Keys. He was born in 1916 in

Shellman,

Georgia. He was working there in a sawmill for 40 cents a day, when in

about 1932, he and a friend decided to come to Miami. Later they

hitchhiked

to the Keys. In Newport, now known as Hibiscus Park, when anyone asks

about

the old times, they all say "Go ask Pop," and that is what I did. When the Navy started installing the water pipeline in the 1940s, Clarence was hired and followed the pipeline, working all the way to Key West. Once the pipeline was completed, he remained in Key West to work for the Thompson Ice Company. It was not long, however, before he came back to Tavernier, where he found work driving a truck for the Comb Fish Company, which was in the vicinity of present-day Mangrove Marina. While driving for Comb, he met Lucienda Williams, whose mother, Rose, a Bahamian, lived on Plantation Key. Lucienda's family had farmed in Planter before her father died. Lucienda was a cook in McKenzie's cafe just north of the Tavernier Hotel. For a while, Clarence also worked there and recalls serving black customers from the cafe's rear window. Clarence decided to move closer to Lucienda's home, so he lived as a squatter in a shack on the Plantation Key Indian mounds where he was the caretaker for Dr. Tallman. He possesses an artifact that looks like a fish. He found it in the Indian mounds that have since been leveled for the Plantation Key Colony housing development. At one time, he had many more artifacts and photos, but sold, gave away or lost them in past hurricanes. Dr. Tallman was a Miami physician, who had a weekend medical clinic at his home on the ocean. For reasons not remembered by Clarence, the doctor decided to close his Plantation Key clinic and remain in Miami. When Clarence had to leave Plantation Key, he considered buying a lot in Newport. Black Bahamian Father Joseph Anderson was selling lots to blacks cheaply enough to make them affordable. Father Anderson was a minister of a black Bahamian orthodox church and was living in Newport when Clarence first came to the Keys in 1932. Father Anderson, wife Margaret and daughter Frances are listed in the 1900 census. Because Dr. Tallman was moving back to Miami, he assisted Clarence in buying a little one-room house on U.S. 1, next door to Father Anderson's home and packing house. It is still there, but a rock addition has since been added. Dr. Tallman had also given Clarence some old, run-down trailers from his property on Plantation Key. Clarence moved those trailers up to Newport, placed them all around his house and started renting them. About this time, Clarence and Lucienda decided to make it legal and marry, he thinks about 1950. Lucienda was a good restaurant cook, and both of them worked. They had two children to care for. Clarence and Lucienda used to visit Bahamian Tom Lowe, Jr. who farmed just south of Ocean Reef. Tom was known by many as he always extended a hearty wave and big smile to all while making the curve to and from Miami. This was before the 18-mile stretch was paved, so all traffic went via Card Sound. Stepping back a little in time, Father Anderson's wife died so he decided to move to Miami. He left his Newport house to Olivia, one of his two daughters. Later, Olivia also moved to Miami. Her children used the Newport house so infrequently that it eventually collapsed from non-use. On February 6, 1992, Clarence showed me where the corners of the Anderson house were and the three sets of concrete steps in the woods behind his trailer. Father Anderson had three other children: Eleanor, "Slim" and Lawrence. Clarence is affectionately called "Pop" and with his permission, I will take this liberty. Pop's first vehicle was a Model-A Ford truck. Later, he bought a 1941 Chevrolet truck with a blown engine, and a gentleman with a peg leg, known only as "old man Pope", brought down a used replacement engine from Homestead. Mr. Pope's "rolling store", a red pick-up truck with a wooden cover and scales hanging off the rear, was a familiar sight in the Upper Keys. Pop's first car was a 1949 Packard. He had a car, two trucks and some rental trailers. He would haul anything the trucks could support, to hauling water from Homestead for a dollar a barrel when there was a drought. Harry Davis' mother Florence and grandmother "Ma Brown" lived farther south than Clarence. The Davis family was from Andros and had farmed the Newport area since the early 1900s. Pop remembers teaching Harry Davis, Jr. how to drive his old Model-A truck in the field where he grew rock melons, banana melons, tomatoes, et cetera. Harry was to become the first black fire chief of Key Largo in 1971. Pop and Lucienda were doing quite well until she developed cancer. Pop took her to doctors in Miami Beach, Miami and Key West. She died in 1955. One of the last things she did was to help circulate a petition to get a school in Newport for the black children. Eventually an old railroad building from Islamorada or Tavernier became the Burlington School with grades 1 to 9. To cover all his wife's medical expenses, Pop had to sell the house and all other possessions. Broken in heart, but not in spirit, Clarence lives in a trailer on the spot where the Father Anderson house was and where today he sells produce on the side of the road. He always has a smile and a good word. Now for the second interview. Mrs. Kathleen Dean was born in Key West, the first child of Louise Dean. Kathleen does not remember much about her father, but her grandmother Elizabeth came to Key West from the Bahamas. Her younger brother, Daniel, was run over by an auto in Key West and killed. She does not know where the next youngest brother, William, is, but her youngest sister, Sandastine, now lives in Miami. When Kathleen Dean was 21, or 22, years old, she went to Homestead on the Flagler train. She did not find a job there, so she came back to Upper Matecumbe to work for Alonzo Cothron doing cleaning work. Later, she moved to Tavernier where she worked for Hubert McKenzie's wife as a cleaning lady. It was while she was working there that the 1935 hurricane struck the Keys. At the beginning of the storm, all the black women were in one of McKenzie's buildings alongside the movie house, now the Tavernier Hotel (mile marker 91.8). At some point, the gusting wind blew the roof off. Fortunately, none were injured and they all ran to an empty boxcar sitting on the railroad siding. The men helped them up into the boxcars. It was a dark and noisy night, but everyone survived without injury. After the hurricane, Commissioner Harry Harris' wife, Peggy, opened a restaurant on the ocean side of U.S. 1 and Kathleen Dean was a cook there for many years. She says that Mr. Harris built a small house in Tavernier for her to live in. By 1950, she was living in a little house in back of the Tavernier light plant, which she thought was going to be sold. She also was aware that Bahamian Father Anderson was selling lots cheaply in Newport, so she obtained a lot and moved into an old, used trailer. A few years later, she became seriously ill and was not able to hold down a full-time job. When she recovered, she discovered that she could eke out a living selling produce, provided that it was good and priced right. Kathleen still lives in what she considers to be the community of Newport. On highway U.S. 1 and farther south than Kathleen Dean, lives Doris Taylor, daughter of Fanessia (Mackey) Taylor. Doris met and married Lawrence Anderson in Miami. They had a son, Peter, who was born in 1948. In 1948, Doris and Lawrence moved to Newport to live with his father, the Bahamian minister Father Joe Anderson, who owned and farmed a considerable tract of land in Newport. At that time, Father Anderson lived in the big house on the corner of what is now Hibiscus Lane. After about a year, Lawrence decided to move back to Miami; he'd had enough of farm work. His father had a rather large grove of limes, sapodillas and about everything that would grow in the Keys. The Bahamians had brought from the Bahamas tried-and-proven plant seeds for this type of farming. Doris and Father Anderson had to tend the groves, pick and pack the fruit, plus ship it to Miami for sale. Some was also sold alongside the then two-lane Overseas Highway. Doris liked living in the Keys, and because her father-in-law was getting on in age, she remained in Newport. Like Clarence Alexander, who was on Plantation Key at this time, she remembers the Gibson family farther up the highway on the curve. Across the highway lived a gentleman identified only as "Smokey." Harry Davis' grandmother Justina Brown, lived about where Scotty's Lumber Company is now (later she moved across the highway). Harry Davis' parents, Harry, Sr. and Florence, lived about a half-mile farther south and owned land where the telephone tower is now. The Saunders and Nina Forbes lived on the gulf side of the highway. Nina Forbes' house has been moved three times. First it was about a mile south bayside, then bay side about where Scotty's Lumber is and finally directly south of Clarence Alexander's. Father Anderson obtained his groceries from Homestead. In later years, the blacks could buy groceries from the rear window of a house-type grocery store owned by Lenny Bethel across from the present Key Largo post office. Lawrence moved back with Doris in Newport. They both went back to Miami after about a year. It wasn't long, however, before she took Peter back to Newport to her father-in-law's house, which she considered to be a good place to raise her son. Also, by now Father Anderson was getting on in years and could really use some extra help with the groves. He had two daughters at home then, so along with Doris they managed fairly well. Father Joe Anderson died in 1952. The late Hector Emmanuel Clark lived two or three houses farther south of Doris just past the church. Later the church burned, but the steps are still there. Hector was a black Bahamian who came to Miami from Grand Turk Island in 1924. He traveled back and forth to Key Largo until he settled permanently in Newport in 1933. He is quoted as saying of the 1935 hurricane, "I didn't lose anything. I had nothing to lose." It is during this time that neighbor Hector Clark fell gravely ill and there was no one to care for him. Doris carried food to Hector, washed his clothes, and generally cared for him. But again she moved back to Miami. She continued to come down on weekends to care for Hector until she finally married him. Hector Emmanuel Clark recovered fully and together they cleared three acres for a farm in back of their first house near the old cistern. From the farming money, they bought the house where she now lives with her son William and his wife, LaTrice. Hector continued farming until he could no longer do so. He arranged the planting of the beautiful rows of poincianas on each side of the road to Herbert and Donna Shaw's house in Pennekamp Park. Doris had three children, Clarence, Peter and William. Her oldest son, Clarence, attended the Burlington School, which is now a church next to the building that houses Mosquito Control Maintenance. Peter Anderson attended Coral Shores High School and eventually became a ranger at Pennekamp Park. He is now the ranger captain at the Highland Hammock State Park in Sebring, Florida. William, the youngest son, graduated from Coral Shores in 1984. He was the one who escorted me to the ruins of Newport, where he had played as a boy. Presently, he is a security guard at the Holiday Isle Resort. Hector Emmanuel Clark, perhaps the last of the Keys farmers, died on November 24, 1987. Doris continues to maintain her household in their house in Newport.

In the mid 1950s many other families, like the Johnsons, Mitchells and

Williams, moved to Newport to contribute to the saga of black heritage

in modern Newport. In 1971, Harry Davis, Jr. became the first black Key Largo Fire Chief and died September 18, 1989. Andrew Flowler was the first black to graduate from Coral Shores High School in 1966. Newport is now known to most as Hibiscus Park, the name of the 1957 housing plat filed by C. R. Skogreth. Newport is once again becoming a center of commerce with the newly built Trade Winds Shopping Center, Friendship Park and the Monroe County housing development. -----End------ Return to General Keys History Index |