|

THE BAHAMAS By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

THE BAHAMAS By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

Like the Florida Keys, indigenous Indians settled the Bahamas long before

the whites came. The following is a brief history of the Bahamas with occasional

references to the Keys.

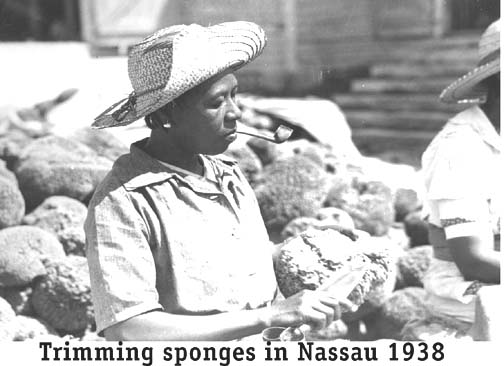

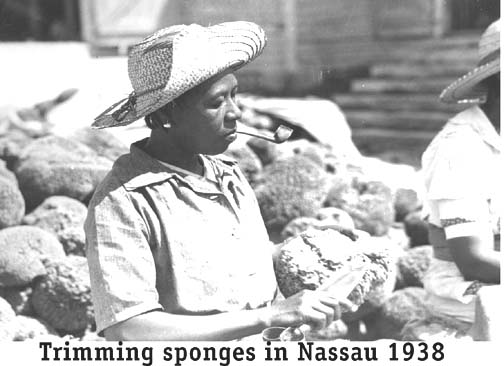

To understand the evolution of Keys history, the Bahama Islands should be considered. The seafaring Bahamian people greatly influenced the settling of the Florida Keys. The 200-mile stretch of islands just off the Florida coast stretching to Haiti is the Bahama Islands. The water there is relatively shallow. "Baja Mar" is Spanish for shallow sea. The Spanish letter "J" is pronounced like the English letter "H." This sounds like Ba-Ha-Mar. Since the land masses were islands, the end result was Bahama Islands. When Columbus became the first Bahamian "tourist," he called the inhabitants "Indians," but they called themselves Lucayans, which means "Island People." They were descendants of the Arawaks of Hispaniola. Pandora-like, Columbus opened the door to "their world." Soon the Spanish entered and decimated the Arawaks of Hispaniola. They forced -or lured- the Lucayans into slave labor on Hispaniola, destroying the entire indigenous race. The Spanish brought to Florida a West Indies native word, "Cacique," pronounced "Ka-SEEK-ee" by some, but "Ka-SEE-eh" by the Spanish, meaning Chief. The fierce Caribe tribe, Spanish for cannibal, gave rise to the name Caribbean. Much the same religious dissension that caused the Pilgrims to sail to Plymouth Rock in 1620 caused Captain William Sayle and 25 others to form "The Company of Adventurers for the Plantation of the Island of Eleuthera." They drew up Articles and Orders and sailed to Eleuthera in the Bahamas in 1648. New Providence became the population center for its central location. It also had a good harbor (Gnaws) with two entrances/exits and was inhabited primarily by seafarers. The sea was a better food source than the island's barren land was for the farming Eleutherans. The Bahamians probably developed the commerce of wrecking, i.e., salvaging goods from wrecked ships. They were intense at their work and nothing stood between them and fortune, often even the surviving crew members. The wreckers made temporary harbors throughout the 700 islands, but Gnaws was their home port. Soon the Bahamian economy started to deteriorate. The "wrecking" turned to "privateering" which degenerated into "pirating." In October 1703, a combined force of French and Spanish sacked and burned Gnaws. It was quickly rebuilt and continued to be the home for hundreds of "Black Flags" of the likes of Blackbeard. This is not to slight two other famous Bahamian pirates, Mary Read and Ann Bonney. It is said they dressed like men, fought like devils and were unsurpassed in bravery. The Bahamas prospered until the onset of the American Revolutionary War, when both England and America took everything they could from the Bahamas to fight each other. After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, many of the English Loyalists (Tories) fled Georgia and the Carolinas either to Florida (then English-owned), or to the Bahamas. The Treaty of Versailles in 1783 restored Florida to Spain, and a great number of these transplanted Florida Loyalists had to flee to the Bahamas to remain under the British flag. By 1788, about 9,300 Tories had fled to the Bahamas and more would follow, but they all had tasted life in the U.S. Before the influx of the American Loyalists, there were probably no more than 1,000 slaves in the Bahamas. There were many Free Blacks who were either exiled from Bermuda, or had escaped to the Bahamas. Bermuda appears to have been uninhabited until 1609 when the British ship Sea Venture wrecked. The ship was transporting English men and women to the Jamestown Colony. The 1776 influx of Loyalists quickly brought in 3,000 or more slaves and the 1783 influx attracted 1,000 more. They started cotton plantations on Crooked Island, the Bahama Lumber Company on Andros Island, a large salt mine on Great Inagua Island, and provided stevedores for all over the world. Florida became a U.S. Territory in 1821, and in 1825, the U.S. decreed that all wrecked goods in the area must be taken to a U.S. port of entry. Key West and St. Augustine were ports of entry. This prompted many Bahamians to move to Key West. (It also prompted Jacob Housman in 1831 to buy Indian Key and attempt to have it declared an official port of entry in competition with Key West.) The U.S. Civil War of 1861-1865 aided the economy of the Bahamas. The Bahamians were expert blockade-runners, but this economic boost ended in 1865 with the end of the war. A killer hurricane struck the entire chain of islands further deteriorating the economy the next year. Effective lighthouses and modern steamships began to replace the older sailing vessels, resulting in fewer shipwrecks. This brought on a decline in the wrecking industry. Sponging and pineapples began replacing wrecking as a business, as they did in the Keys also. The population of the Bahamas rose from 39,000 in 1870 to 53,000 in 1900. The Flagler railway extended to Key West in 1912 and brought in cheap Cuban pineapples. This doomed not only the Bahama pineapple market, but also that of Planter and Plantation Key. One in five Bahamians departed for the U.S. The Bahamas fared well in World War I with its shipping expertise and were helped greatly in 1919 by the passing of U.S. Prohibition. Commerce once more boomed as the result of ships acting as rumrunners. Gun Cay, Cat Cay, Bimini and West End were all within 60 miles of Florida, but, as with all booms, it came to an end. In 1933 Prohibition was repealed. However the Bahamas had prospered and its population had risen to 60,000. Late in 1938, a deadly malady struck the sponge industry, but the tourist industry flourished. Britain granted self-government to the Bahamas in 1964. In 1967 Lynden Pindling and his Progressive Liberal Party won control. The Bahamas gained independence from Britain on July 10, 1973. The new nation was admitted to the United Nations the same year. -----End------- Return to General Keys History |